The Environmental Case For Free-Range Livestock?

This disconnect between our dietary lifestyle and the reality of nutrition compromises personal health and imperils the planet. As more people have become aware of the damaging environmental effects of producing livestock and animal products, many have made a concerted effort to brand free-range livestock products as more healthful and sustainable.

Is this an effort to greenwash the livestock industry, or should we be working to incorporate livestock into climate change mitigation strategies? What are the associated opportunity costs relative to other mitigation strategies?

When we account for the effects of livestock on personal health, land and resource usage, and missed opportunities, the notion of free-range livestock as a climate solution appears dubious at best. The following video produced by Table (formerly the FCRN) summarizes the findings of a landmark study conducted in partnership with the University of Oxford and many other organizations.[2]

To summarize: although there is evidence that holistic grazing practices can reduce the net carbon emissions from free-range livestock production, that reduction is marginal compared to the overall contribution of greenhouse gasses from the livestock sector. Even with these practices in place, livestock’s outsized contribution to greenhouse gas emissions and climate change would continue.

Furthermore, the marginal reduction in emissions is relatively small compared to the carbon sequestering potential of other solutions. For instance, restoring agricultural lands to a more natural forested environment would return greenhouse gasses into forests and soils at a much higher rate. In effect, rewilded agricultural lands could serve as a carbon sink, absorbing the vast majority of greenhouse gasses emitted up until now.

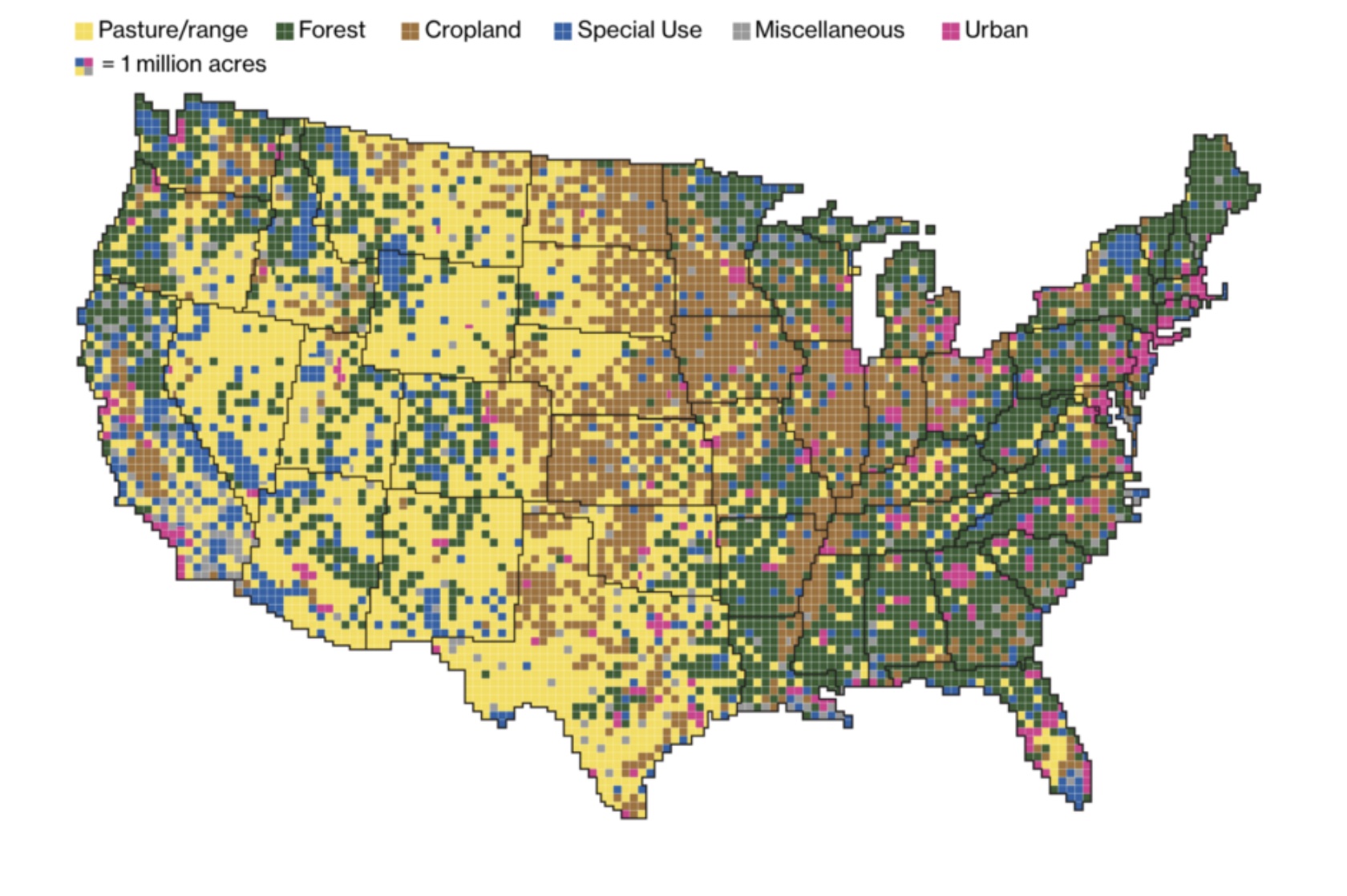

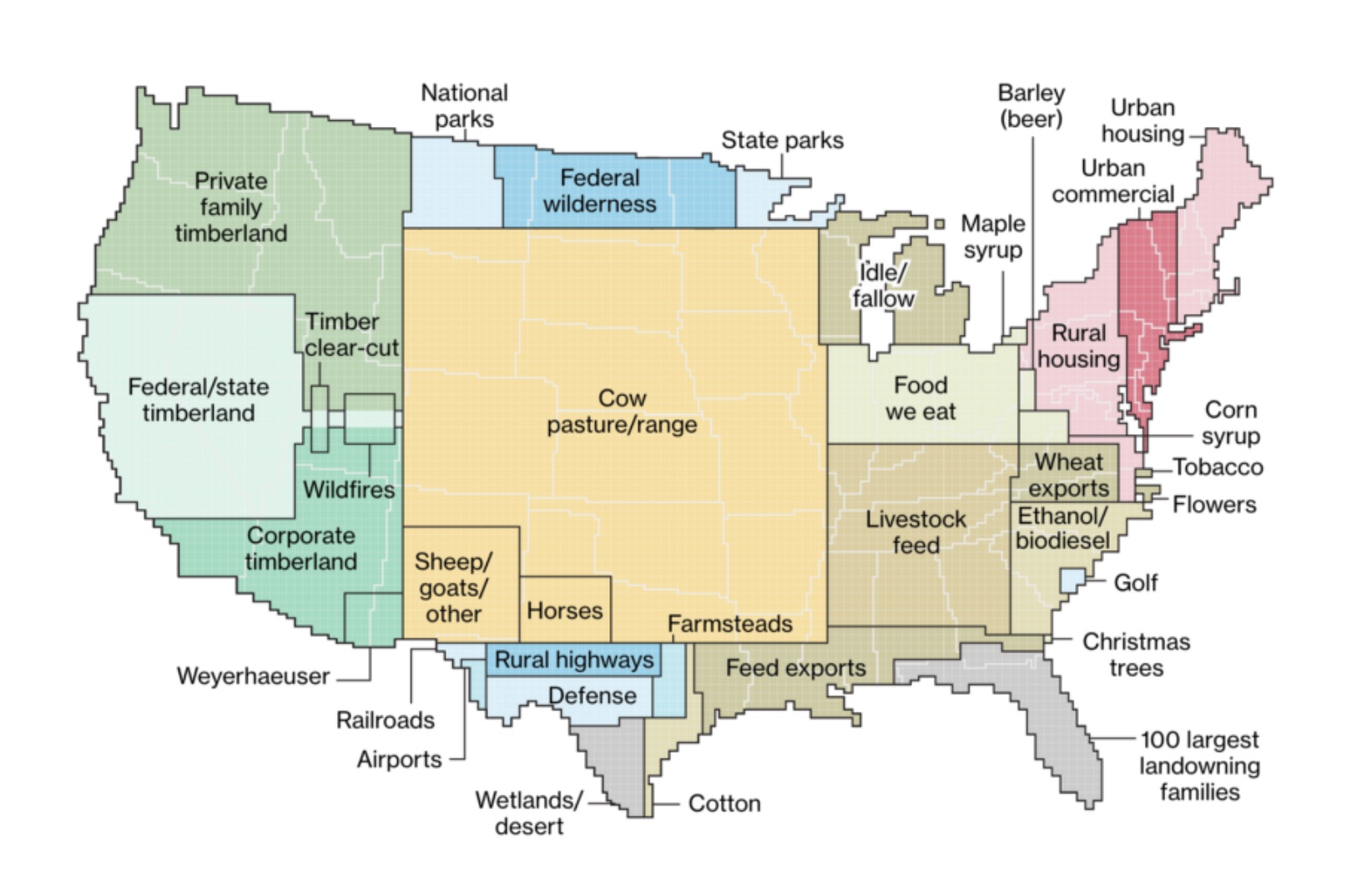

Soil carbon sequestration can be one of the most impactful strategies in mitigating climate change. This requires solutions that simultaneously lower agricultural land requirements and minimize emissions as much as possible. That means reducing the amount of land used for livestock grazing and feed (currently 41% of land in the contiguous US), which contributes disproportionately to agricultural land use. In terms of land use requirements, free-range livestock would be a step backward. To supply the current amount of animal protein from free-range sources would require an estimated 2.5 times the current landmass utilized for livestock.[3] Even if this expansion of agricultural land were possible, it would exacerbate our impact on the environment and the climate. As it happens, this expansion is impossible: there is not enough land to support the current level of consumption of animal products if we were to transition toward free-range products. This “sustainable” option is incompatible with the reality of current dietary patterns.

Conversely, a shift in land use toward plant-based alternatives could feed an extra 4 billion people just by utilizing the agricultural land currently in production for livestock. Below we can see a visualization of how land is currently used in the United States and globally.[4][5] Notice how much land is used for livestock grazing and feed and the nutritional returns for utilizing such a large landmass. Notice the differences between how many people are fed from livestock sources as opposed to their plant-based counterparts and their relative land usage.

While there are potential environmental benefits of transitioning toward free-range livestock, they are limited and only apparent compared to current industrialized concentrated animal operations. Compared to the benefits of plant-based foods or rewilding, the benefits of free-range livestock are marginal at best. Furthermore, this “solution” would continue to fuel seven of the top ten leading causes of death worldwide. By instead moving beyond a system driven by animal agriculture, it is possible to support a growing population, utilizing less land for agriculture and allowing for rewilding and reforestation to combat climate change while also providing better nutrition.

References

- Berg J, Jackson C. Nearly nine in ten Americans consume meat as part of their diet. Ipsos. May 12, 2021. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.ipsos.com/en-us/news-polls/nearly-nine-ten-americans-consume-meat-part-their-diet

- Garnett T, Godde C, Muller A, Röös E, Smith P, de Boer IJM, zu Ermgassen E, Herrero M, van Middelaar C, Schader C, and van Zanten H. Grazed and Confused? Ruminating on cattle, grazing systems, methane, nitrous oxide, the soil carbon sequestration question – and what it all means for greenhouse gas emissions (2017). FCRN, University of Oxford. https://www.oxfordmartin.ox.ac.uk/downloads/reports/fcrn_gnc_report.pdf

- Rowntree JE, Stanley PL, Maciel ICF, Thorbecke M, Rosenzweig ST, Hancock DW, Guzman A, Raven MR. Ecosystem impacts and productive capacity of a multi-species pastured livestock system. Front Sustain Food Syst. December 4, 2020. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsufs.2020.544984

- Merrill D, Leatherby L. Here’s how American uses its land. Bloomberg. July 31, 2018. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://www.bloomberg.com/graphics/2018-us-land-use/

- Ritchie H, Roser M. Land use. Published online at OurWorldInData.org. September 2019. Accessed January 3, 2023. https://ourworldindata.org/land-use